Emigration causes vets shortage in South Africa – The Mail ...

Veterinarians leave the country or enter private practice for economic reasons, which puts state vets in rural areas under more pressure. (Getty Images)

South Africa has a shortage of veterinarians because they are leaving the country for better prospects abroad, with those left behind struggling to plug the gap.

Most of the exodus has occurred in rural regions, undermining the care of livestock.

The president of the South African Veterinary Association, Paul van der Merwe, said the rate at which veterinarians are leaving has picked up, with more than 100 vets emigrating each year.

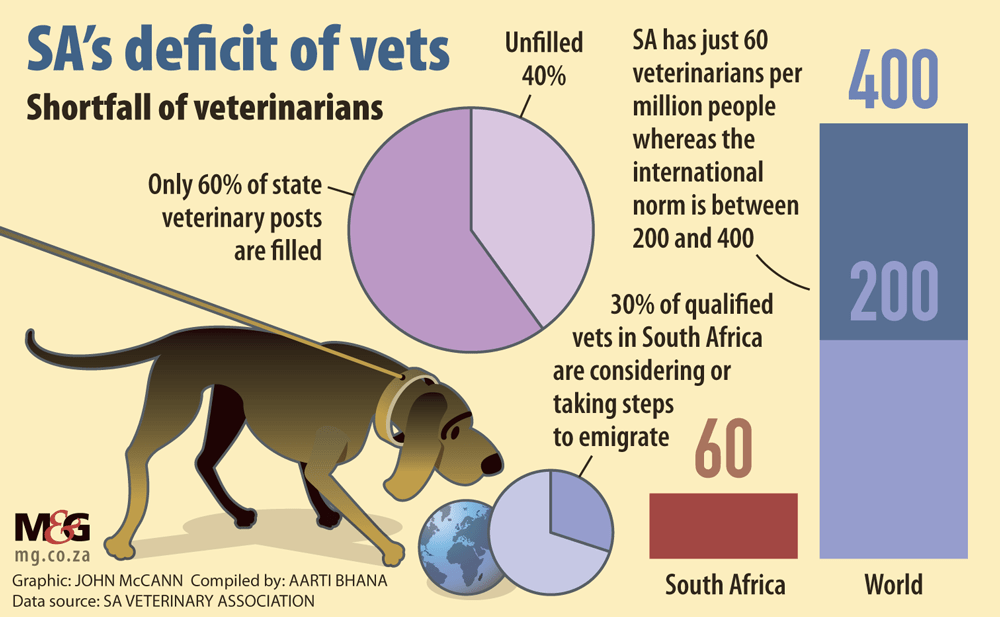

He said the international norm is for 200 to 400 veterinarians per million of the population, but South Africa has only 60 veterinarians per million. In addition, the veterinary association receives frequent reports of practices closing in rural areas, either for financial reasons or because of staff shortages.

“With a shortage of veterinarians in rural areas, the health and welfare of production animals cannot be guaranteed anymore, with a direct impact on food safety and security, which in turn has a direct impact on the health and well-being of humans,” Van der Merwe said.

“Furthermore, disease control and biosecurity are not optimal, with failures in the system leading to disease outbreaks such as foot-and-mouth disease, African swine fever and avian influenza, to name a few. This has the potential to spill over to humans, as could be seen with Covid-19.”

According to a 2022 survey by the veterinary association, the majority of qualified vets leaving the country were younger than 25. It said 21% of people aged 25 to 29 had already begun the emigration process, while 38% indicated being fairly certain of emigrating, even if only for a limited period. Only 41% said they were willing to stay in South Africa.

Reasons for the exodus include safety, security and economic concerns, career growth, the working environment and the regulation of veterinary services.

Van der Merwe said all this was despite “huge” interest in the field.

“The faculty of veterinary science receives far more applications than they can accommodate. They have a very strict selection process. Unfortunately, the selection process is no guarantee that more veterinarians would like to work in rural areas,” he said.

Of concern was that only 60% of state veterinary posts were filled.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)Tod Collins, a vet of more than 50 years who works with cattle and other large animals in KwaZulu-Natal, said the departure of veterinarians was a worrying trend.

“The offers they get from overseas financially, we battle to match them here in South Africa at the moment, and they are much stricter with their working hours, and the physicality of their work seems to be a lot less stressful compared to the South African vets; and remuneration packages are very tempting for young vets to go across there to pay off student loans,” he said.

“It’s making the vets that are in the country work even harder because they are fewer doing the amount of work that they should be more vets for.”

Collins said this was also leading to unskilled people filling some positions.

The compulsory community services programme places 140 veterinarians every January. Some get absorbed into the sector but others choose to go abroad, said Dipepenene Serage, the deputy director general for agricultural production, biosecurity and natural resources management at the department of agriculture, rural development and land reform.

“Our concern is that most of our newly qualified vets are absorbed by the private sector or other countries. Yes, there is a shortage, but it’s not dire,” he said.

“What is important is that at the moment farmers are able to access veterinary services. Farmers in communal farming setups are serviced by state vets. So far we are managing, even though the shortage puts some strain on the current workforce. There are plans to have another additional university to offer this qualification, which at the moment is offered only by the University of Pretoria.”

Veterinarians in rural regions earn less than those in the city, and many of them have started trading in medicine or animal remedies with farmers to help supplement their income, but this is not sustainable and could contribute to more people leaving the sector, Collins said.