Archbishop of Cape Town makes 'urgent' request for details of ...

AMONG the Makin review’s conclusions is that John Smyth, who continued to beat and abuse boys after moving to Zimbabwe in 1984, was “a problem solved and exported to Africa”. It recommends the establishment of “international reciprocal safeguarding procedures with other Anglican Communion institutions/leaders, including protocols for informing overseas Anglican leaders and statutory authorities, where there are allegations against a person in position of trust and they relocate abroad”.

It also recommends that the Church consider further independent reviews of the abuses, and potential abuses, perpetrated in Zimbabwe and South Africa, where Smyth moved in 2001, after being refused re-entry to Zimbabwe. At least 85 boys and young men were physically abused in these countries. The Makin review concludes that he perpetrated this abuse “likely up until his death in August 2018”. In the last months of his life, he was worshipping at an Anglican church, St Martin’s, in Cape Town.

The failure to prevent the abuse began in the 1980s. There is, the review says, “no evidence that any proactive attempts were made to alert authorities in Zimbabwe” by the Church of England clergy, such as the Revd David Fletcher, who had seen the 1982 “Ruston Report” documenting Smyth’s crimes. By the time attempts were made, Smyth had already begun his abuse.

“The starkest fact is that the UK abuses should have been pursued further, reported to the UK police and pursued by them,” it says. Mr Fletcher, and others, “deliberately and knowingly, stood in the way” of a police investigation.

The review also documents failures to alert authorities in Africa after 2013, when the diocesan safeguarding adviser in Ely, and other church officers, including the then Bishop of Ely, the Rt Revd Stephen Conway, and the Archbishop of Canterbury, were officially informed about Smyth’s abuse. During this period, a survivor was urgently seeking assurance that efforts were being made to prevent further abuse in South Africa but was told that no further action could be taken.

In August 2013, Bishop Conway (now Bishop of Lincoln), wrote to the then Bishop of Table Bay, the Rt Revd Garth Counsell — a suffragan bishop in the diocese of Cape Town, where Smyth was residing — alerting him to Smyth’s abuses. He received a letter of acknowledgement, stating that the Bishop was in conversation with the Rector of the parish that John Smyth belonged to, and that he would consult with the Archbishop of Cape Town, Dr Thabo Makgoba. The letter said that Bishop Conway would be “kept informed”, but the diocese of Ely has said that no further correspondence was received (News, 10 May 2019).

After receiving this acknowledgement, Bishop Conway said that he “[did] not think that much action would be taken”. He told the review that he did “all within my authority as a Bishop of the Church of England. . . I had no power to pursue that authority.”

The safeguarding adviser in the diocese of Ely, Yvonne Quirk, told the Makin review that she then made repeated attempts to establish contact with the Bishop’s safeguarding adviser in South Africa (“I think there were three emails, none of them acknowledged”). Bishop Conway told her that he had attempted “several times to make direct bishop-to bishop contact and had no response either”. Ms Quirk — who has apologised for not taking further action — told the victim that she had “no power to compel agencies in South Africa to respond to my concerns”.

The Makin review records that the letter to Bishop Counsell was discussed by the National Safeguarding Team in 2017, who agreed that the Anglican Church of South Africa should be “handed further information” through the Anglican Communion Office. It is, it says, “unclear if any follow up with South African counterparts took place because of the Core Group discussions”.

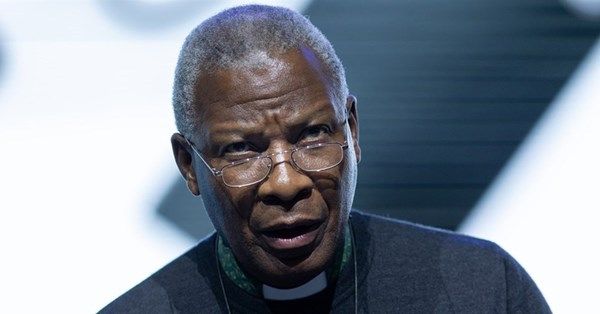

“There was a failure, by senior Church leaders, to ensure John Smyth was not able to further abuse victims,” it says. The Archbishop of Canterbury “could and should have reinforced the message to the Church in Cape Town via his friendship with Thabo Makgoba”.

This week, Bishop Conway said: “In 2013, in following the safeguarding advice, policy and practice of that time, I believed that I had done all I could and that the allegations were being responded to appropriately.” He understood, however, that that there were “further actions I could have taken”.

The Makin review states that Smyth attended His People Church in Glenwood, Durban in 2002, and then Church on Main from 2004 until his removal in 2016.

In 2019, a spokeswoman for the office of the Archbishop of the Anglican Church of Southern Africa said that, after receipt of Bishop Conway’s letter in 2013, they “heard nothing about Mr Smyth or his whereabouts for the ensuing four years”.

On Wednesday, Dr Makgoba’s office said that he had requested “as a matter of urgency” a “detailed timeline of events”.

“Bishop Counsell was told by St Martin’s Parish in Cape Town, either in 2013 or 2017 or both, that John Smyth had worshipped there for ‘a year or two’ after first coming to Cape Town,” a statement said. “We now believe this would have been before 2005. Bishop Counsell was told by the parish that Smyth had not counselled any young people, nor had they ever received any report that he had abused or tried to groom young people. Smyth was never licensed for any ministry, whether youth or other, in the parish.

“Upon reviewing the matter at the Archbishop of Canterbury’s request in 2021, my office learned from St Martin’s that Smyth had been permitted to worship in St Martin’s in the last months of his life, on condition that he was not to get involved in any ministry or contact any young person. He attended services from sometime after October 2017 until his death in August 2018.”

The Makin review identifies as a possible factor in the failures that took place after 2013, “the lack of procedures for safeguarding across the Anglican Communion”. In 2016, a new protocol was agreed, establishing a system whereby bishops share information about alleged and proven criminal conduct and sexual misconduct of clergy and lay leaders who move between/within provinces. It would not have applied to Smyth, who is not recorded as having applied to undertake authorised ministry in South Africa.

In 2022, the Archbishop of Canterbury told a Lambeth Conference session on safeguarding that safeguarding was “the biggest and most painful burden of this role that I have faced over the last ten years . . . the biggest scandal I have been dealing with is around a married conservative Evangelical” (News, 5 August 2022).

Speaking to The Times this week, a survivor of Smyth’s abuse in Zimbabwe, said that he felt the abuse had been “exported by the UK to us”.